It was a military idea at first – deflating the tires on army vehicles that landed on the beaches of Europe in the Second World War made it easier to drive them on the sand. Now, 70 years later, the technology has come to the fields of Ontario farms.

Only now, the concept of running tires at low pressure is not just about traction, it’s also about keeping soil and crops healthy.

Jake Kraayenbrink has farmed with his family near Moorefield, Ont., since 1989. With 300 acres plus custom work, he combines 1,000 acres in total, as well as raises pigs that are in demand internationally as breeding stock. With too much manure for his land base, Jake’s curiosity is often drawn to exploring creative ways of applying and maximizing the value of manure. He uses only manure, no fertilizer, on his own farm.

“Manure is good for fertility, and it contains live organisms that are needed for cropping,” said Jake.

While he has always used large tires and put the manure on when the crop most required it, he realized that compaction from heavy manure tankers may take away the benefit to the soil.

What if he deflated the tires?

After a research trip to Europe, where he discovered the concept had been in practice for more than 20 years, Jake decided he wanted to use tire deflation technology at home. Some farmers, especially from Holland, wouldn’t even allow machinery in their fields without deflation systems.

Reducing the tire pressure on large farm machinery not only gives better traction on soft soil, but it also reduces compaction, reduces fuel consumption and extends tire life.

The research

Jake and his research team visited a European machinery manufacturer who had these systems already in place for farm machinery, but wasn’t willing to service the North American market.

So Jake looked west, where the tire inflation and deflation concept was in use in the trucking industry. On cement trucks or logging trucks, for example, lowering the tire pressure gave a two-wheel drive truck the ability to move across a jobsite even more easily than a four-wheel drive under difficult, soft conditions.

Re-inflating the tires allowed that same truck to be driven back on the road.

The technology was available from a trucking firm in Western Canada but the system was too extravagant and time-consuming, taking almost three minutes to work. Farmers just can’t spend that kind of time at the side of a field.

Meanwhile, the word was getting out in the press about the concept of tire deflation on farm machinery, and Nuhn Industries Ltd. got an order for a tanker with a deflation system, a system that did not yet exist. Kraayenbrink saw an opportunity.

With the help of two capable neighbors – Maurice Veldhuis, a ventilation engineer, and Steve Bailey, a truck mechanic – they took a truck system apart, starting right from the valve stem. Truck tires aren’t the same as farm tires – trucks have high pressure, low volume; farm tires have low pressure, high volume.

It took all winter but the trio developed a system that could deflate tires in 25 seconds – a “huge breakthrough,” said Jake. Their new system, the Automatic Air Inflation Deflation control device, known as AAID, has three components:

- An air delivery system with a quick release valve that releases air right at the valve stem,

- An air supply system – compressor and tanks – that started with 30 horsepower, 105 cubic feet per minute and went to 10 hp, 36 cfm. The one-third smaller system uses less hydraulic oil to work and needs a smaller storage tank, and

- An air control box in the cab with digital readout and pre-set tire pressures adjusted by a toggle switch. “You don’t have to do anything but flip the switch,” said Kraayenbrink.

There is also a box with manual override – all quick attach. Should there ever be an issue with electronics you can still inflate and complete the job, said Kraayenbrink.

It takes about 30 seconds to deflate the tires from 35 down to 15 pounds per square inch; as the tires get hot the system adjusts itself to keep the pressure right.

Certain components of the system can be moved, and the components are all quick attach. You can move the compressor in about 40 minutes if you want to, from your tanker to your baler or solid spreader.

Kraayenbrink’s research started in 2009. By 2011, he was ready to go commercial, and his company, called AgriBrink, was opened for business. Developed with funding assistance from the Farm Innovation Program, the invention earned him an Ontario Premier’s Award for Agri-Food Innovation Excellence in 2011.

The benefits

Two tire tracks are spray painted on a plywood board at a manure demonstration day at Kraayenbrink’s farm in August 2012. The first shows a footprint of 600 square inches at 35 psi; the second shows the footprint of the same tire deflated down to 15 psi, showing 961 square inches of surface area. The larger surface area means the equipment won’t sink as deep in soft soil and compaction is reduced as the weight of the load is spread over a larger surface area.

Last year in Ontario was really wet and Kraayenbrink said he got stuck with their tankers, but when they deflated the tires really low he was able to get out. The commercial spreader got stuck too, but pulled through with deflated tires as well.

“I wouldn’t have believed it went right through the wet holes – like putting duals on a tractor, or putting on snowshoes,” reported Kraayenbrink.

Tire deflation is mainly about compaction and traction, but fuel savings and tire life factor in as well.

It takes less fuel to pull a deflated tire, something that Kraayenbrink proved for himself in his own field trial. With tires inflated and a full fuel tank, Kraayenbrink drove on the road 20 minutes. He then deflated the tires to field inflation level, filled the fuel tank and did the same run, using 14 percent less fuel.

“If you’re using 30, 40 or 50 litres per hour you can knock off four to five litres of fuel, saving money and the environment,” said Kraayenbrink.

Tires are expensive too. Tire pressure is determined by speed and weight – the slower you go, the less pressure is required – and Kraayenbrink estimates they get 60 to 80 percent more life when the pressure is optimized.

“Tires last longer because you always have your tire pressure optimized – you’re not compromising.”

Also, you always know your tire pressure, he says – you can’t visually see an abnormally low tire, but with a monitor in cab, a low tire can be detected early. It doesn’t happen often but when it does happen it costs a lot of money.

Financially, you can measure such things, but compaction is harder to measure. Researchers have found that damage attributed to compaction can stay in the soil for more than 10 years. Some years it won’t show – if it’s wet or there is the right amount of moisture, crop roots don’t need to go as deep. But if it’s dry, the roots need to look deeper for moisture, and compacted soil will get in their way. The effects of compaction are greater on clay soils or those low in organic matter, but using lower tire pressure will help any soil type, by reducing compaction or by helping to alleviate compaction.

“There are a number of benefits we’ve come to learn about,” Kraayenbrink reports, that will become more of a feature as equipment gets bigger. As he says, land is getting too expensive to work at a reduced potential.

The future

“This could go a lot further – we’ve been using it on any machinery we can get it on,” said Kraayenbrink.

It’s not just for manure tankers; it can be used for anything that goes on the road and field. Manure is one of the heavier items to cross over the field so it’s when transporting it that the effects are most noticeable.

Determining the ideal pressure requires knowing your weight and speed and the tire manufacturer. A heavy 12,000-gallon tanker may go from 40 psi to 20 psi, while a 5,000-gallon tanker may go from 28 to 14 psi, for example. On a big sprayer, 65 psi can go down to 40, allowing the unit to work optimally for its design.

Right now, the AAID control will do just one set of tires, on the implement, but Kraayenbrink took the opportunity at the manure demo day to unveil his latest control unit that can do tires separately on the tractor and on the implement. He had just finished setting it up the night before.

“It’s always dangerous to come out with something new when you’re still working on it,” admitted Kraayenbrink, but he’s excited to report that by spring, he will have a unit available that will be able to do up to four different sets of tires.

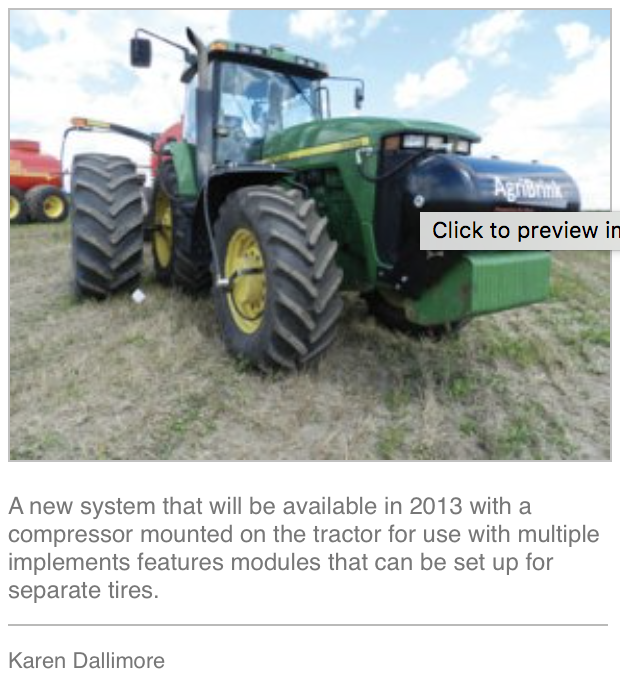

“We’ve put a compressor on the tractor – we can inflate and deflate the front, back and trailer tires as required to increase the footprint,” he told the crowd.

“By reducing tire pressure, we’re reducing compaction, reducing injury to soil and crop, and increasing our fuel efficiency,” said Kraayenbrink.

He predicts that as soil health becomes more of a concern and more studies show the effects of compaction, practices such as tire deflation will become more accepted.

“There are a lot of interesting things in today’s agriculture,” said Kraayenbrink. “Change is going to happen.”

For more information on Jake Kraayenbrink and his company, AgriBrink, visit www.agribrink.com or call 519-840-0919